Susannah Gillespie, the wellness and group fitness manager at the York JCC, shares recovery techniques in momentum.

After any challenging workout, a nice cool down period with some stretching is often just what your body needs and is an important time to transition. Individuals living with Parkinson’s Disease (PD), however, have additional challenges beyond what your typical gym goer might face. People diagnosed with PD may have “bradykinesia, rigidity, tremor, impaired balance and coordination of movements” (Malling, 2018). So how can we help our participants achieve greater recovery? We designed a trial evaluating movement speeds as an indicator of improved recovery. While movement speeds improved, we found that overall movement quality may have been an even better benchmark of recovery.

In March, we asked for volunteer participants from the Momentum neurocognitive movement disorder group at the York JCC to test out two types of recovery technologies. Each individual was asked to perform two of our standard assessments: a three meter timed up and go test (TUG) and a three meter backwards walking test. For four weeks, individuals attended three Momentum group fitness classes. After two classes each week, the participants stayed after class to use either the Normatec or PEMF mats.

The Normatec leg sleeves were used on one participant for 20 minutes each session. This tool provides external dynamic compression to help increase blood flow to the area as well as help to drain lactic acid away from the legs.

The PEMF mat was placed into a chair and the participant would sit on the mat for 20 minutes each session. The science behind PEMF, or pulsed electromagnetic field therapy, demonstrates cellular recovery by “increasing the ‘charge’ of the cell’s electrons” (Bryant, 2019).

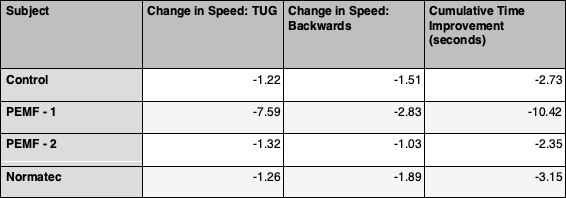

At the end of the four weeks, participants were re-assed in the same manner as done initially. For the individuals using the PEMF mat, their TUG scores improved by 15.2 to 7.61 seconds and 4.47 to 3.15 seconds. Walking backward, times improved from 11.68 to 8.85 seconds and 6.63 to 5.60 seconds. For the individual using Normatec, TUG scores improved from 7.02 to 5.76 seconds, backward walking from 10.71 to 8.82 seconds. We also measured one person not participating in the recovery sessions to use as a control subject. His TUG improved from 4.02 to 2.81 seconds and his backward walking 5.82 to 4.31 seconds.

While the sample size limited any overall conclusions from speed of movement, it was noted by both participants and instructors an improvement in the quality and confidence in movement in the participants utilizing recovery devices. The individual chosen for the Normatec was selected to use that particular tool due to visible challenges in his leg mobility. At the end of the trail, we noticed significant progress in his lateral hip flexibility and ankle mobility. The individual recorded under PEMF-1 data, one of our oldest participants, displayed an increased length in stride and stability in his regular movements. If we are to repeat this trial, some additional variables we would like to document and measure would be stride length, lateral walking stride length, non-motor symptoms and perceived mood.

When we initially designed the protocol, we anticipated each individual using their recovery tool to do so alone in our assessment room. In actuality, they ended up sharing space most of the time. Fixed in one position for twenty minutes at a time, three times each week for four weeks allowed the participants to enjoy time together talking. Another symptom of Parkinson’s Disease is increased occurrence of depression and anxiety or a combination of both (Chang et al, 2020). Combining the physical benefits of both exercise and recovery sessions along with the psychological benefits of socialization at the same time help with mood elevation. There exists “an association among motor status, mood fluctuations and brain dopamine levels” (Canesi et al, 2020).

References

- Bryant, S. (2019). The Wide-Ranging Benefits of Pulsed Electromagnetic Field (PEMF) Therapy. Positive Health, 255, N.PAG.

- Canesi, M., Lavolpe, S., Cereda, V., Ranghetti, A., Maestri, R., Pezzoli, G., & Rusconi, M. L. (2020). Hypomania, depression, euthymia: New evidence in Parkinson’s Disease. Behavioural Neurology, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/5139237

- Chang, Y.P., Lee, M.S., Wu, D.W., Tsai, J.H., Ho, Pei-Shan, Lin, C.H.r, Chuang, H.Y. (2020). Risk factors for depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A nationwide nested case-controls study. PLoS ONE, 15 (7)

- Malling, A. S. B., Morberg, B. M., Wermuth, L., Gredal, O., Bech, P., & Jensen, B. R. (2018). Effect of transcranial pulsed electromagnetic fields (T-PEMF) on functional rate of force development and movement speed in persons with Parkinson’s disease: A randomized clinical trial. PLoS ONE, 13(9), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204478